Old Devonshire House

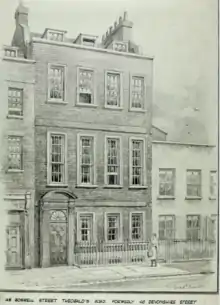

Old Devonshire House at 48 Boswell Street, was located between Theobald's Road in Bloomsbury, and Queen Square, London. William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire had the house built in 1668 for his son, also called William Cavendish, who was MP for Derby at that time and eventually became the 1st Duke of Devonshire in 1694.[1] This house was later sold by William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire, who built Devonshire House in fashionable Piccadilly. Major George Henry Benton Fletcher bought Old Devonshire House in 1932,[2][3] to display his keyboard collection.[4] He donated the house and his collection to the National Trust in November 1937. The house was destroyed in May 1941 by a Luftwaffe bombing raid on Holborn during the Blitz. Most of his keyboard instruments had been evacuated to Gloucestershire before the raid. These survived and are currently on display in Fenton House, Hampstead.

Architecture

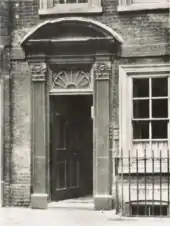

Old Devonshire House was Stuart-period brick-constructed house built in 1668 shortly after the Great Fire of London in September 1666. The house was built according to the regulations of the Rebuilding of London Act 1666, which laid down the new rules for domestic accommodation.[5] This act was drafted urgently to eliminate factors, which had caused the fire.[6] The house was specified as a "Second Sort" type, with three storeys plus basement and garret.[7] Brick or stone construction was mandated, with cellar brick width 2½ br., 'first' and 'second' storey 2 br., 'third storey 1½ br. and garret minimum 1br.[5] The house was elegantly proportioned with the first and second storey 10 feet in height. The four tall second storey front windows unusually featured nine panels in the upper, and six in the lower casement, which gave the large front drawing room an imposing appearance. Fluted pilasters with flattened Corinthian cornices framed the mahogany front door with a fanlight and arched pediment above. Behind the front door a hall led to a broad straight staircase to the first floor. The architect if any is unknown. William Talman (architect) who designed Chatsworth House for the Devonshires was only 18 in 1668.[8] Nicholas Barbon[9] might have been involved. He built Red Lion Square, close to the site of Old Devonshire House and Pepys House at 14 (and 12) Buckingham Street,[10] two of the few surviving Stuart houses built in London after the Great Fire. 41 and 42 Bedford Row [11] are ascribed to him and are closely similar in facade to Old Devonshire House. Nicholas Barbon was known to have been involved with the alteration of the Devonshire’s Bishopsgate property in 1676.[12]

Cavendish occupancy, 1668–83

William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire 1640 - 1707 occupied this house from 1668-1683.[1] He was a Member of Parliament for Derby and a leader of the anti-court and anti-Catholic party in the House of Commons. He moved to Montagu House, Bloomsbury on the current site of the British Museum. His political support for the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688, which brought William III of England to the throne, was rewarded with the title of Duke of Devonshire in 1694.[13]

Old Madam Legh and her family's occupancy, 1687–1729

Elizabeth Legh, widow of Richard Legh moved to London, with her two eldest married daughters, taking a lease on this Devonshire House after her husband's death in 1687. Elizabeth, who came to be called "Old Madam Legh", belonged to the family of the Leghs of Lyme, who owned Lyme Park in Cheshire, England, from 1398 until 1946, when the house and gardens were given to the National Trust. She was able to gather round her influential people in the society of the day. James Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormonde, William Stanley, 9th Earl of Derby and his wife Lady Elizabeth Butler, Lord Colchester, Hugh Cholmondeley, 1st Earl of Cholmondeley were friends and habitués of the house, which became a sort of centre for the leading lights in the political and social world during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain.[14] Old Madam Legh died in 1728 aged 85 and her will left the lease of the London house to her granddaughter Elizabeth together with her pew, No.48, in St George the Martyr, Holborn, for which she paid a rent of £2 5s a year. Some of the contents of Old Devonshire House including portraits of herself[15] and her husband Richard[16] by Peter Lely, "a great Japan cabinet", "A black Ebaney Cabinet inlaid with jeuery" and some garden furniture including lead cupids were transferred from London to Lyme Park and are still there in the custodianship of the National Trust.

Occupancy from census returns, 1841–1911

The census returns of 1841-1911 indicate the number and occupation of the tenants at 10 year intervals.[17] The numbers of occupants increased from 5 in 1841 and 6 in 1851 to 25 in 1861, 28 in 1871,19 in 1881, 31 in 1891, 10 in 1901 and 12 in 1911. During this period, the majority of the tenants worked as craftsmen or tradesmen some using their rooms as workshops. An upholsterer and cabinet maker with a sideline as an auctioneer, an engineer and a linen draper lived there in 1841 are followed in 1851 by a lathe and toolmaker, a barrister's clerk and a house servant. In 1861 the occupations included a map engraver, a retired customs officer, a coach trimmer, a clerk to a navy agent, a servant, a musician and a carpenter. The 27 occupants in 1871 included a printer and his apprentice son, a retired ship's captain, an optician, a solicitor's clerk, a porter, a medical practitioner called Francis Berrington, who lived at this address for more than 30 years, an unemployed milliner and a woolen draper, also unemployed. In 1881 the occupations mentioned included a gun engraver called Richard Pope, a picture restorer, an unemployed printer compositor, a journeyman plasterer, a teacher, a bookbinder and a 15 year old embroideress. In 1891 the occupations mentioned included a cabinet finishing father and son, a cab driver's groom, a tailor and a paper embosser; the doctor and gun engraver were still present. In 1901 a stationer, two actors, a soap traveller and the gun engraver are mentioned. In 1911 three families included the gun engraver, his wife and daughter who was a perfumer's shop assistant, a family of four tailors, an apprentice architect and an apprentice tailoress and a blacksmith, William Prince and his son an assistant and daughter.

Benton Fletcher's occupancy, 1934–41

Benton Fletcher's radio talk, "Early Music at Old Devonshire House", published in The Listener (magazine) in 1937 described the occupancy when he bought Old Devonshire House in 1934: "Thirty-five men, women and children were living in about a dozen rooms: a family of seven crowded into one room, and in another an old man, who bolted his door against all comers, made and mended his own shirts, but to everyone’s surprise died leaving over £100,000 in the bank.[4]" A 300-year lease on 48 Devonshire Street was sold to Benton Fletcher in February 1934 by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (S.P.A.B). This Society had purchased the building in 1932 from Bertram Hawker, the previous owner, with a view to preserving and using the building for its offices and also hoping to protect other historic buildings in the street. Benton Fletcher recalled in Sept 1938; "It was entirely through Mr Humphrey Talbot"[18][19](a vice-chairman of the SPAB), "whom I had known as a small boy that I heard of the house which he had discovered after the death of the owner Mrs Hawker whose family I happened to know."[20] Benton Fletcher was "searching for a suitable building with the right atmosphere, in central London, where lovers of old music might study and practise on early keyboard instruments.[4]"

In September 1937, the journalist and poet Hubert Nicholson[21][22] wrote "it was bought three years ago by Major Benton Fletcher, who has not only transformed its appearance, restored its ancient magnificence, hung Delft on the wall of one room, a Gainsborough in another and furnished it with fine Caroline and Jacobean chairs and other interesting antiques, but has housed in it his unique collection of old musical stringed instruments."... "Other collections of this kind are dead," Major Benton Fletcher said. "Mine is alive. Students and fine musicians come here to play these instruments - often there is music in four rooms simultaneously".[23]

In November 1937 The Times[24] reported: "Under the scheme for saving country houses of historic or architectural value, which was described in The Times of April 7, Major Benton Fletcher has presented Old Devonshire House, Bloomsbury, to the National Trust, subject to his life interest, a gift of some appeal to architects, furniture connoisseurs, and musicians". This announcement at a luncheon held at the Criterion Restaurant by the National Trust was recognised as a pivotal moment in the Trust's history as speakers pleaded for a national effort to preserve as many as possible of existing historic country houses.[25] Vita Sackville-West said that, "taking the long view, the only future for the great homes of England and even for the small manor houses of the Cotswolds, was to bring them inside the fold of the scheme propounded by the National Trust".[24] The publicity in the press associated with his gift of Old Devonshire House to the National Trust led to an invitation to wireless broadcasts,[26] a television appearance with instruments[27] and a visit from Queen Mary (Mary of Teck). The Court Circular for The Times 3 June 1938 records: "Queen Mary, attended by the Hon. Margaret Wyndham, honoured Major Benton Fletcher with a visit to Old Devonshire House, Bloomsbury, yesterday afternoon and expressed her interest in the collection of musical instruments and antique furniture."[28]

Benton Fletcher's development of Old Devonshire House into a school for early music, a concert hall as well as a museum of early keyboard instruments was described by Edgar Hunt. "The Major invited me to join in his efforts to start a conservatoire for early music. I had studied the viol with Edmund van der Straeten and was ready to teach any viol players as well as recorder, while Mr Hinchcliffe looked after the harpsichordists and madrigal singers...my recorder pupils were transferred from Trinity College of Music.",[29][30]

References

- Stephen Denford and David A Hayes, Streets East of Bloomsbury, Camden History Society, 2008, pp 26-27

- Old Devonshire House, 48 Devonshire Street, W.1. The Residence of Major Benton Fletcher: Country Life, 17 April 1937, lxxx-lxxxiv

- Benton Fletcher, Old Devonshire House, Bloomsbury, Apollo Magazine, Vol XXV11, no. 161, May 1938, pp 242-244

- Benton Fletcher, "Early Music at Old Devonshire House", The Listener, 6 October 1938: pp 713-714, issue 508

- T. F. Reddaway, The Rebuilding of London After the Great Fire, 1940, p 80 Jonathan Cape, London

- "BBC - History - British History in depth: London After the Great Fire". Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- "Terraced house - London Historians' Blog". Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- John Harris, William Talman Maverick Architect: George Allen and Unwin, London, 1982, ISBN 0-04-720025-1 Pbk

- R. D. Sheldon, ‘Barbon, Nicholas (1637/1640–1698/9)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 20 November 2015

- "Buckingham Street - British History Online". Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- http://www.bloomsburylives.co.uk/project/walk-3/

- Margaret Sefton-Jones, Old Devonshire House by Bishopsgate. 1923, London: The Swarthmore Press Ltd, Ruskin House, 40 Museum Street, WC1, London p 139

- Roy Hattersley, The Devonshires, The Story of a Family and a Nation, Chatto & Windus, London 2013, ISBN 978-0099554394

- Evelyn Caroline Legh Newton, The House of Lyme from its foundation to the end of the eighteenth century: William Heinemann, London 1917 pp 355 - 386

- Possibly Elizabeth Chicheley, Mrs Legh, by Jacob Huysmans, (Antwerp c1630 - London 1696), Lyme, Cheshire, NT 499976 http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/499976

- Richard Legh (1634-87) by Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680), Lyme Park NTPL Ref. no. 63852, http://www.ntprints.com/image/344603/richard-legh-1634-87-by-sir-peter-lely-1618-1680

- The Census Returns for England for 48 Devonshire Street, Parish of St George the Martyr, Middlesex 1841--1911, The National Archives

- Obituary. The Times (London, England), Tuesday, 7 March 1944;

- Roger and Julia Bolton, A Family at War, The Talbots of Little Gaddesden 2013 Grosvenor House Publishing Limited, ISBN 978-1-78148-636-8

- Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings archive, Devonshire Street folders, 37 Spital Square, E1 6DY

- Hubert Nicholson. The Times (London, England), Tuesday, 16 January 1996; pg. 21; Issue 65477.

- http://www.bloodaxebooks.com/ecs/category/hubert-nicholson accessed 31/03/2016

- Hubert Nicholson, The Bazaar Exchange & Mart, Tuesday, 14 September 1937

- Old Devonshire House, The Times (London, England), Friday, 19 November 1937; pg.20; Issue 47846

- "Preservation Of Old Country Houses." The Times [London, England] 9 July 1938: 17 issue 48042.

- Fletcher, Benton. "Early Music at Old Devonshire House." The Listener [London, England] 6 October 1938: 713+, 8.0 Thursday 29 September, which was repeated on Tuesday 20 December,10.45 Thursday and 23 2 March 1939. The Listener Historical Archive. Web. 4 January 2015

- TV Script for 29 December 1937, National Trust Inventory number 3075290 Fenton House

- The Times (London, England), Friday, 3 June 1938; pg. 17; Issue 48011

- Hunt, Edgar. "A Harpsichord Odyssey (11)", The English Harpsichord Magazine, vol.3, no 1, 1981

- "Notes and News". The Musical Times, 79.1148 December 1938, p 935