Treatise on Relics

Treatise on Relics or Tract on Relics (French: Traité des reliques) is a theological book by John Calvin, written in 1543 in French about the authenticity of many Christian relics. Calvin harshly criticizes the relics' authenticity, and suggests the rejection of relic worship. The book was published in Geneva, and was included in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[1][2]

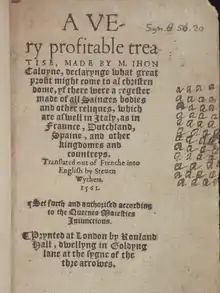

Front page of the 1599 Geneva edition | |

| Author | John Calvin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Traitté des reliques: ou, advertissement tres-utile du grand profit qui reviendrait a la chrestiente s'il se faisait inventaire de tous les corps saincts & reliques qui sont tant en Italie qu'en France, Alemagne, Espagne & autres royaumes & pays |

| Translator | Stephen Wyther (1561), Henry Beveridge and M. M. Backus (1844), Valerian Krasinski (1854) |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Language | French |

| Publisher | Pierre de la Rouiere |

| Media type | |

Background

The cult of saints and their relics, unfamiliar to early Christianity, became widespread in Anglo-Saxon England. The worship of saints and their relics began in fourth-century Rome, when Christians begin to dig up the bones of their saints for worship; this was opposed by the priest Vigilantius, who was opposed in turn by Jerome. By the end of the 4th and 5th centuries, the cult of relics had grown to include secondary objects such as clothing. Real and fake relics were kept in churches, monasteries and royal houses, and were widely traded; the trade in relics increased after the Crusades. Even fake relics were richly decorated with gold, silver, and precious stones for display to pilgrims who considered them authentic. By the mid-16th century, the number of relics was enormous and it was nearly impossible to determine a relic's authenticity. Guibert of Nogent's early-12th-century On Saints and Their Relics (Latin: De sanctis et pigneribus eorum) was a critique of popular religion and the alleged relics in the Abbey of Saint-Médard de Soissons, a Benedictine monastery which was destroyed during the French Revolution.[3] The Reformation criticized the veneration of saints and relics, and 1543 Calvin published his Tract on Relics in response to Albert Pighius' 1542 "De libero hominis arbitrio et divina gratia libri X" (which opposed Calvin and Martin Luther).

Contents

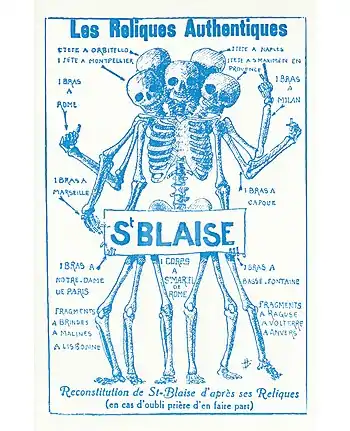

Calvin described relics from 12 cities in Germany, three cities in Spain, 15 cities in Italy, and 30-40 cities in France. He asserted that fake relics had been traded since Augustine's lifetime, and had increased as the world inevitably became more corrupt. Calvin proposed to abandon the veneration of relics, citing God's hiding of Moses' burial place in the Old Testament book of Deuteronomy (34:6). According to Calvin, God hid Moses' body so the Jews would not fall into idolatry (which he equated with the veneration of relics). Calvin listed in detail the falsified Christian relics known to him, which were kept in churches and monasteries. According to him, saints had two, three or more bodies with arms and legs; extra limbs and heads also existed. Calvin did not understand where the relics of the Biblical Magi, the Bethlehem babies, the stones which killed Stephen, the Ark of the Covenant, or Aaron's two rods (instead of one) came from. Objects of worship included Jesus' robe and a towel with which he wiped himself. The relics had several copies, in different places. Others included a piece of fish which Christ ate after the resurrection, Christ's footprint on a stone, and his tears. Cults of hair and the Milk of the Virgin were widespread. The combined quantity of Mary's milk was so great that, according to Calvin, only a cow could produce that much. Other objects of Marian worship were a very large shirt, two combs, a ring, and slippers. Relics associated with the Archangel Michael were a small sword and shield with which the disembodied Michael defeated the disembodied spirit of the Devil. At the end of the treatise, Calvin warned the reader:

And so completely are they all mixed up and huddled together, that it is impossible to have the bones of any martyr without running the risk of worshipping the bones of some thief or robber, or, it may be, the bones of a dog, or a horse, or an ass. Nor can the Virgin Mary's ring, or comb, or girdle, be venerated without the risk of venerating some part of the dress of a strumpet. Let every one, therefore, who is inclined, guard against this risk. Henceforth no man will be able to excuse himself by pretending ignorance[4]

Translations

The Treatise on Relics has been translated into a number of languages. Twenty editions were published between 1543 and 1622: seven in French, one in Latin, six in German, two in English and four in Dutch.[5] In 1548, it was translated into Latin by Nicolas des Gallars and published as Admonitio, Qva Ostenditur quàm è re Christianae reip. foret Sanctorum corpora & reliquias velut in inuentarium redigi : quae tam in Italia, quàm in Gallia, Germania, Hispania, caeterísque regionibus habentur in Geneva.

Calvin's book was translated into German in 1557 and published by Jacob Eysenberg in Wittenberg as Vermanung von der Papisten Heiligthumb: dem Christlichen Leser zu gute verdeudschet;[6] it was published in Pforzheim in 1558, and in Mühlhausen the following year. Another German translation, by Johann Fischart, was published in 1583 in Strasbourg as Der Heilig Brotkorb Der H. Römischen Reliquien, oder Würdigen Heiligthum[b]s procken: Das ist, Iohannis Calvini Notwendige vermanung, von der Papisten Heiligthum[b] : Darauß zu sehen, was damit für Abgötterey vnd Betrug getrieben worden, dem Christlichen Leser zu gute verdeutscht.[7] Calvin's book was translated into Dutch in 1583 and published in Antwerp by Niclaes Mollyns as Een seer nuttighe waerschouwinghe, van het groot profijt dat die Christenheydt soude becomen, indien een register ghemaect werde van alle de lichamen ende reliquien der Heylighen, die soo wel in Italien, als in Vranckrijck, Duytschlant, Hispanien, ende in andere conincrijcken ende landen.[8]

The first translation into English, by Stephen Wythers,[9] was published in 1561 in London as A very profitable treatise made by M. Ihon Caluyne, declarynge what great profit might come to al christendome, yf there were a regester made of all sainctes bodies and other reliques, which are aswell in Italy, as in Fraunce, Dutchland, Spaine, and other kingdomes and countreys.[10][11][12] An 1844 translation by M. M. Backus was published in New York as Calvin On Romish Relics : Being An Inventory Of Saints' Relics, Personally Seen By Him In Spain, Italy, France And Germany.[13] That year, Henry Beveridge translated Traitté des reliques for the Calvin Translation Society as An Admonition showing, the Advantages which Christendom might derive from an Inventory of Relics; it was published in Edinburgh. Another translation, by Walerian Krasiński, was published in Edinburgh in 1854 as A Treatise on Relics. The book was published in Italian in 2010 as Calvino 'Sulle reliquie': Se l’idolatria consiste nel rivolgere altrove l’onore dovuto a Dio, potremo forse negare che questa sia idolatria?[14][15]

Legacy

Calvin published his Treatise on Relics as part of the Reformation, and Protestants abandoned the veneration of relics. Although Reformed denominations have removed representations of saints from their churches, Lutherans permit images of saints but do not worship them.

Jacques Collin de Plancy published his three-volume Critical Dictionary of Relics and Wonderworking Images (French: Dictionnaire critique des reliques et des images miraculeuses), partially based on Calvin's work, in 1821–22.[16][17][18] The saints were arranged in alphabetical order, and each entry identified how many of their bodies were in different churches. The entries for Jesus and Mary listed relics in a number of monasteries which included hair, the umbilical cord of Christ, and the hair and nails of the Virgin Mary. In his 1847 book Curiosities of Traditions, Customs and Legends (French: Curiosités des traditions, des moeurs et des légendes), partially based on Calvin's work, Ludovic Lalanne compiled a table listing the number of heads, bodies, hands, feet and fingers attributed to each saint.[19] Émile Nourry used Calvin's work to describe Jesus' relics (which included a tooth, tears, blood, an umbilical cord, a foreskin, beard and head hair, and nails) in the 1912 Les reliques corporelles du Christ.[20][21]

References

- Радциг Н. И. «Traite des reliques» Кальвина, его происхождение и значение / Сборник «Средние века», №01 (1942) / Ежегодник РАН / Издательство: Наука.

- Philip Schaff. «History of the Christian Church» / Volume VIII / HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION. 1517 – 1648./ THIRD BOOK. THE REFORMATION IN FRENCH SWITZERLAND, OR THE CALVINISTIC MOVEMENT. / CHAPTER XV. THEOLOGICAL CONTROVERSIES. / § 122. Against the Worship of Relics. 1543.

- "Medieval Sourcebook: Guibert de Nogent: On Relics". Fordham University. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- An Admonition showing, the Advantages which Christendom might derive from an Inventory of Relics (1844) by John Calvin, translated by Henry Beveridge

- Carlos M. N. Eire. War Against the Idols: The Reformation of Worship from Erasmus to Calvin. Cambridge University Press (1989), p. 229

- Johannis Caluini Vermanung von der Papisten Heiligthumb: dem Christlichen Leser zu gute verdeudschet

- Johann Fischart

- Netherlandish Books (NB) (2 Vols.): Books Published in the Low Countries and Dutch Books Printed Abroad before 1601 / Andrew Pettegree, Malcolm Walsby/ BRILL, 2010 / p. 286 || 6435

- Stephen Wythers arrived in Geneva in 1556; his brother, Francis, was a deacon of the English church in 1557. After returning to England, Stephen published a translation of the Traité des reliques.

- Bibliographia Calviniana: catalogus chronologicus operum Calvini : catalogus systematicus operum ... by Alfred Erichson (1900), p. 22

- A very profitable treatise made by M. Ihon Caluyne, declarynge what great profit might come to al christendome, yf there were a regester made of all sainctes bodies and other reliques, which are aswell in Italy, as in Fraunce, Dutchland, Spaine, and other kingdomes and countreys. Translated out of Frenche into Englishe by Steuen Wythers. 1561. Set furth and authorised according to the Queenes Maiesties iniunctions

- Andrew Pettegree, «Calvinism in Europe, 1540-1620». Cambridge University Press. 1996 / p. 90

- Calvin on Romish relics : being an inventory of saints' relics, personally seen by him in Spain, Italy, France and Germany

- Sulle reliquie

- Trattato sulle reliquie

- Dictionnaire critique des reliques et des images miraculeuses Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy T 1

- Dictionnaire critique des reliques et des images miraculeuses Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy T 2

- Dictionnaire critique des reliques et des images miraculeuses Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy T 3

- Curiosités des traditions, des moeurs et des légendes, 1847./ page 123

- Saintyves, P. Les reliques et les images légendaires. Le miracle de Saint Janvier, Les reliques du Buddha, Les images qui ouvrent et ferment les yeux, Les reliques corporelles du Christ, Talismans et reliques tombés du ciel, Mercure de France, 1912, 340 p. / "Les reliques corporelles du Christ"/ p. 107-184

- Журнал "Атеист" `1925 № 10 / стр. 63-81

Further reading

- Радциг Н. И. «Traite des reliques» Кальвина, его происхождение и значение / Сборник «Средние века», No.01 (1942) / Ежегодник РАН / Издательство: Наука.

- Philip Schaff. «History of the Christian Church» / Volume VIII / HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION. 1517 – 1648./ THIRD BOOK. THE REFORMATION IN FRENCH SWITZERLAND, OR THE CALVINISTIC MOVEMENT. / CHAPTER XV. THEOLOGICAL CONTROVERSIES. / § 122. Against the Worship of Relics. 1543.

- Peter Brown The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (The Haskell Lectures on History of Religions)/ SCM Press, 1981 / p. 7

- The Writings of John Calvin: An Introductory Guide / by Wulfert De Greef / Westminster John Knox Press, 2008 / p. 143-144